When we first started working on “Panavor,” we decided to conduct interviews in Istanbul. We planned to physically meet with people who could provide us with information about the culinary culture, and then we planned to conduct online interviews with Diaspora Armenians.

We had already completed some interviews in Istanbul when we started thinking about a trip to Armenia. As we continued with new interviews, we realized how important it was to conduct interviews with people who once lived outside of Anatolia. While conducting interviews in Istanbul, we began contacting and interviewing Armenians living in the diaspora. Along the way, we met many people who helped and advised us, particularly in America, Argentina, Europe, Brazil, Canada, and Lebanon. Nevertheless, we still had no plans to travel outside of Bolis to conduct interviews.

Syrian Armenians in Yerevan

պլօկ

Now, after several months of work, we feel how important it was for us to meet with Armenians living in different parts of the world who share a common culture and feelings.We were so alike and yet so different! While we were interviewing with people from different parts of the world, something struck our attention. Everyone was speaking Armenian with a particular timbre and melody. Hearing these “different” Armenians, recording them, visiting the homes of the people we interviewed virtually, getting to know their families, and forming friendships with people all over the world was an indescribable experience for us.

It is true that during the planning phase of “Panavor” we had some ideas about where we could find different Armenain communities, but as the Turkish proverb says: “The caravan is lined up on the road.” In other words, after we started working on Panavor, we did not hesitate to make changes so that the project could continue more accurately, and we constantly improved ourselves with the feedback we received. Our visit to Hayastan in November 2021 and our meeting with Azniv Stepanyan opened up new possibilities for us. Azniv’s initial response when we told her about Panavor was, “Why don’t you meet with Syrian Armenians while you’re in Armenia?” It was a reasonable question! After that, we immediately decided to interview Syrian Armenians who had emigrated to Armenia, so we requested Azniv’s help in identifying them. We were fortunate to know Azniv because she supported us in reaching numerous individuals and provided guidance.

Journeys and changing spices

All of the individuals we interviewed in Armenia immigrated during the Syrian Civil War. Due to the effects of the recent war, forced migration, and the unavoidable transformation they brought, the interviews with Armenians of Syria differed from other interviews. We once again realized that migration and war transform culture in a significant way.

Accordingly, while the individuals we interviewed in diaspora provided a story that was centered on their family’s recovery from the Armenian Genocide and the cultural transformation they endured in their country of arrival, the stories of Armenians of Syria were shaped by their own migration experiences. Armenians of Syria residing in Armenia claimed that, in contrast to their experiences in Syria, their culture in Armenia is largely restricted to homes as they do not have any cultural institutions. Whereas, our interviewees who are living in the diaspora stressed the importance of maintaining Western Armenian culture through associations, schools, and churches. Dalida Degirmenjian describes this situation in these words:

For example, I remember there were years when during Easter we couldn’t keep up with the demand for chocolate, as many kids and relatives would visit. There were times when my mother in-law had to go back to the market to buy more chocolate, so that we wouldn’t run out of chocolate for our guests. Of course, the kids would eat a lot of chocolate during those days, so it would finish very quickly. That is why we would have a great time during those festive days. We cannot enjoy those occasions we used to have in Syria. In one word, we don’t have those here. Especially when you are left on your own, for example, when your children aren’t with you during the Easter period or the Christmas holidays, it is a bit difficult.

Thus, we had the opportunity to listen to the stories of our interviewees and their families, first to Syria and almost 100 years later to Armenia. Often, the stories of the two migrations were intertwined, and the lines separating them blurred. Every interview we conducted included a migration story. However, the stories of Syrian Armenians were more varied and contained multilayered experiences. For example, if we listen to the story of a family from Antep, we will learn how they migrated to Aleppo during 1915 and then, during the Syrian Civil War, to Yerevan. It’s as if there were no 100-year gap between these two stories.

The Panavor project was started with the intention of building an archive where intangible cultural objects, such as songs, lullabies, and culinary memory, are gathered. With the interviews we conducted for this project, we got the chance to learn about the lives of our interviewees in Syria and in Armenia after their migration. Although it was inevitable that every interview we conducted for Panavor would contain a migration narrative, the narrative of migration in our interviews with Syrian Armenians was multi-layered and contained a variety of migrations. For example, the migration story of Talin Ishanian, whose ancestors were from Urfa and Antep, who was born and raised in Lebanon and lives in Armenia today, was one of the most layered migration stories we have ever witnessed. Talin, who immigrated to Syria after the Lebanese Civil War, was forced to immigrate to Armenia after the Syrian Civil War.

I was born in Lebanon, but my mother and father, more so my mother, are from Höllük. […] When the war started in Lebanon, because of the war, we immigrated to Aleppo. […] We cannot compare life here with life in Aleppo. Life was different there. I am sure life is not the same everywhere. But it is good to be in our motherland.

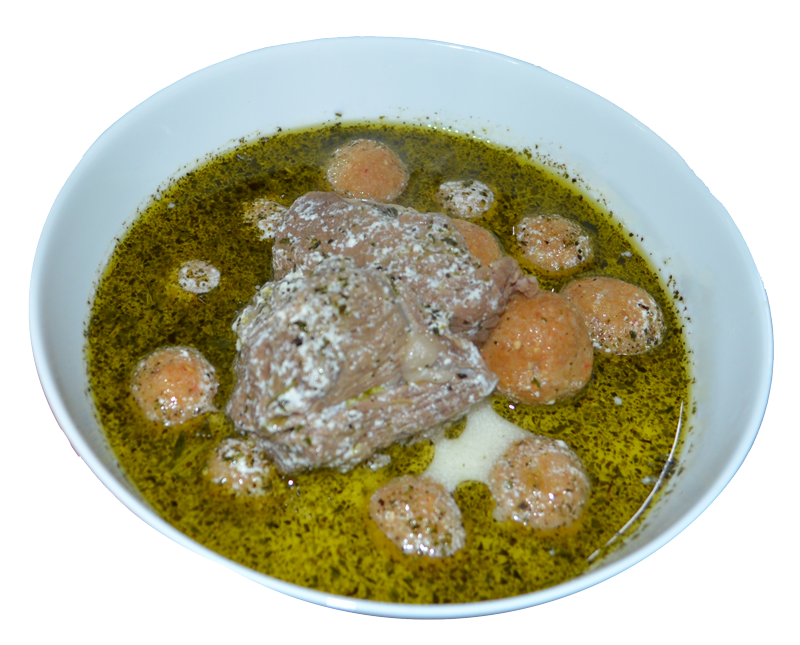

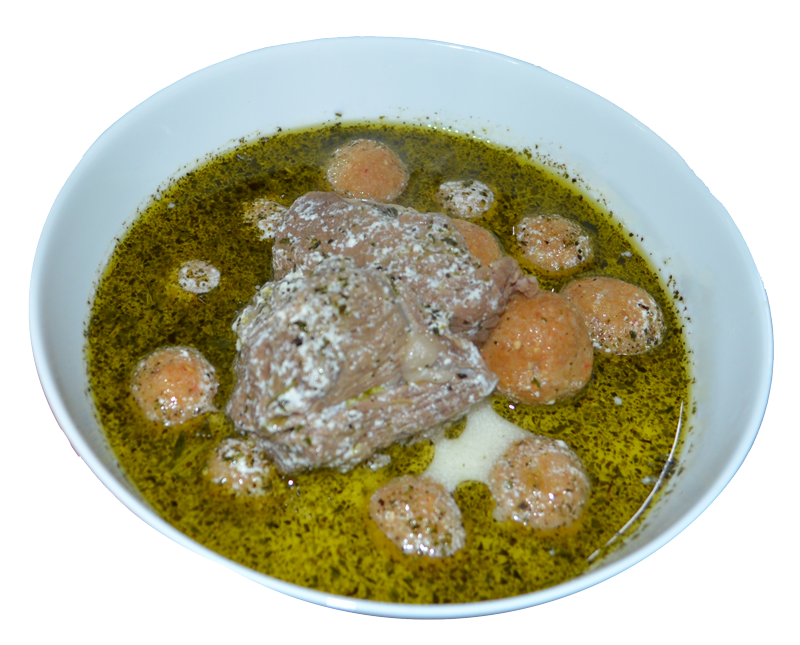

Of course, it wasn’t just the people who migrated; their things and cultures did as well. For instance, “Madzunov kofte,” which was once prepared in Antep’s kitchens, migrated with the cooks who prepared it, and a component of it was adjusted in each city to which it was brought. The story of a family who immigrated from Anatolia to Syria and subsequently to Yerevan is truly reflected in the slightly altering ingredients and recipe of “Madzunov kofte.”

«մածունով քէօֆթէ»ին բաղադրիչները եւ չափը Այնթապէն Հալէպ,

Հալէպէն Երեւան գաղթող ընտանիքի մը պատմութիւնն է։

Dishes, spices, and dairy products were just a few of the things that were changing as a result of the migration and the changing conditions in the country of destination. It was inevitable that the dish being cooked would differ as a result of the changing yoghurt, spices, butter, meat, and other ingredients. In other words, these changes obliged Dalida kooyrig, who welcomed us into her kitchen in Armenian, to try different methods and ingredients for preparing the same dish. As a result, despite keeping its name, Madzunov kofte’s flavour differed from that of Syrian kofte.

Today, many Armenians from Argentina to Lebanon, still cook the recipes they learned from their ancestors in their kitchens. Even though they are thousands of kilometres apart, the foods prepared by these individuals who once resided in nearby villages or provinces still have a similar flavour. Everyone makes Easter buns, for instance, but Armenians from Istanbul make one with gum and mahaleb, influenced by their Greek neighbours, while those who reside in Lebanon and Syria prepare one with different spices. In some cases, this results in serving various Easter buns on the same table. For instance, the Sasun Armenians in Istanbul still prepare their savoury Easter buns in addition to the mastic Easter buns.

Երեւանի մէջ եղողը ի վերջոյ այլ «մածունով քէօֆթէ» մըն է

We conducted a total of four interviews in Yerevan. Three of these were in-depth interviews. In these interviews, through the life stories of our interviewees, we had the opportunity to listen to a period, sometimes even different periods. We were able to record various family histories, customs, cultures, recipes, and Armenian parpars (dialect) during these interviews. We were really fortunate that several of our interviewees cooked the meals they referenced in the interviews for us to taste. We were able to sample borani, madzunov meatballs, samsak urfa, eggplant kebab, and many more in this way.

The story of a family who immigrated from Anatolia to Syria and subsequently to Yerevan is truly reflected in the slightly altering ingredients and recipe of

“Madzunov kofte.”

As a result, despite keeping its name, Madzunov kofte’s flavour differed from that of Syrian kofte.

A cup of coffee has 40 years worthy of remembrance

The desire to return

You know, I was very young when I came here, Narod. When I returned with my husband 15 years ago, we stayed for a month, I satisfied my longing, but I felt that I had changed. That country was no longer a place for me. I saw certain things that I did not like, very basic things. This is how it is. When you leave somewhere and go away, your longing stays but when you return, I don’t belong here and neither do I belong there. Do you understand? I am neither entirely Argentinian, nor entirely Syrian.

During the course of the meal, Roz Tantik read to us a love letter that her great-grandfather had written in Urfa parpar (dialect) with a few Turkish words in it. We were able to listen to and record in Armenian using the Urfa dialect thanks to this letter. For us, listening to Roz Tantik and trying to decipher the letter like a puzzle was an unforgettable experience. When we discussed their present conditions, they expressed a desire to return since they missed the customs, traditions, and culture in Syria.

When we got back to Istanbul, we learned that Antrantik Dayday had passed away and that Roz Tantik had temporarily moved back to Syria. We are incredibly fortunate to have met them, to have dined at their tables, and to have recorded this conversation.

Last remarks

Every interview taught us something new. Investigating, recording, and organizing a person’s family and personal history has the appearance of an excavation. The personal and cultural character of a meal, as well as the proximity formed at the dining table, moved our oral history work into a different emotional zone, and the line between the interviewer and the interviewee became blurred at times.